The following publication is a compilation of student work from “Transformative Botanical Representations” course offered in the Summer of 2024 led by Divine Ndemeye and supported by TA Madelaine Snelgrove. This course is a continuation of the work that took place in the Summer of 2023, linked here. The course invited students to critically challenge modes of documentation and representation of plants in contemporary landscape design discourse. In designing and delivering this course, we were guided by this main area of inquiry:

How can we relate to and document plants in ways that acknowledge their sacredness and agency and lead us to better relations?

Overall, this course engaged students in discourses and practices that disrupt the Eurocentric visual narrative and offer alternative representational techniques, styles, and media that would invite meaningful kinship between humans and plants. Students were invited to employ a multitude of representational methods and ways of working and engaging in critical spatial discourses.

The inquiries of the course were not intended to be a scientific exercise but an ethnobotanical cultural and artistic study. In this course, we are challenged to ask different questions that can guide us toward kinship with plants. All assignments focused on communication and representation as a means of expressing complex critical thoughts and personal narratives through storytelling. Questions and narratives on our positionality, ancestry, culture, intersectionality and critical reflection guided the discussions and work during the course. The works below have been organized by their assignment structure of the class.

Thank you to Madelaine and to all of the students for their work and conversation throughout the course.

- A1: Relational Ethnobotanical Narratives

- A2: Sacred Landscapes & Flora Case Studies

- A3: Garden of Feels

Assignment 1: Ethnobotanical Narratives asks students to pick a plant of their choose and challenge conventional botanical representation in Landscape Architecture by layering relational and cultural meaning. Through different forms of research (embodied, secondary, experiential), students are asked to think and relate to the plant beings from a stewardship, care and reciprocal lens to layer stories and meaning into and unto different modes of representation.

Dean Anesi

Tatianna Duncan

In my mixed media art piece, I chose the weeping willow tree to challenge conventional botanical representation in landscape architecture by layering relational and cultural meanings. This introspective journey, spanning ancient to modern times, reflects the willow’s profound impact on various cultures and my personal connection to this tree. Through this exploration, I aim to foster a deeper understanding and empathy for the weeping willow, highlighting our reciprocal relationship with nature. I used a combination of film roll frames with hand sketches within to represent this passage through time.

The journey begins in ancient China, where the weeping willow’s origins lie. I depicted a traditional wooden lattice window overlooking a willow tree. For the Chinese, the willow embodies grace and strength, bending without breaking. This cultural connection reflects an early stewardship and respect for nature, foundational to the Chinese ethos.

The next window, a small, high mudbrick opening from ancient Babylon, offers a glimpse into the weeping willow’s biblical connection. This scene ties to the Israelites’ exile in Babylon, where they mourned under willow trees by the rivers of Babylon, as mentioned in the Psalms. The willow’s scientific name, Salix babylonica, originates from this narrative.

Transitioning to 15th-century Europe, I illustrated a Gothic window with stained glass, symbolizing the weeping willow’s introduction to the European continent. This period marked the willow’s integration into European gardens, embodying the Renaissance spirit of art and nature’s harmony. The stained glass, casting colourful light onto the willow, reflects the era’s aesthetic and cultural embrace of natural beauty.

The fourth window, from a European settler’s home during the 1700s, signifies the willow’s arrival to North American. The wooden-framed window opens onto a willow tree, symbolizing the tree’s transplantation and adaptation across continents. This era reflects the settlers’ utilitarian and aesthetic appreciation for the willow, integrating it into new landscapes.

Concurrently, a window from the Coast Salish people’s cedar plank house represents the indigenous connection to the willow. The small slat openings overlook a willow, illustrating the practical and medicinal uses of willow bark by the Salish. This scene honors the indigenous knowledge and reciprocal relationship with the willow, emphasizing a deep-rooted respect and sustainable use of natural resources.

The final window, from my childhood home in 2005, opens onto the willow tree that stood outside my bedroom. This personal connection to the willow tree symbolizes my bond with nature and the beauty of the natural world. Growing up with the willow fostered a sense of peace and continuity, making the tree a lasting symbol of home and comfort.

Through these six windows, my art piece encapsulates the weeping willow’s multifaceted journey across cultures and time. By layering historical, cultural, and personal meanings, I challenge the conventional representation of this botanical being. This exercise in stewardship, care, and reciprocity with the willow tree fosters a deeper understanding of our interconnectedness with nature.

Alex Mok

Drawing on umbrella, span 84cm

Mahonia aquifolium, commonly known as tall Oregon grape, is an evergreen, suckering shrub native to regions from British Columbia to California. The genus name ‘Mahonia’ honors the 18th-century American horticulturist Bernard M’Mahon, while ‘aquifolium’ means ‘wet leaf’. This species thrives in early spring with frequent, intense rains in the Lower Mainland, producing vibrant yellow flowers in broad terminal racemes.

The idea of drawing this species on an umbrella symbolizes its status as a common rainflower in Vancouver. The motion of opening an umbrella mimics the blooming of Oregon grape, representing its tendency to flower during rain. Examining closely the drawings reveals the seasonal patterns of this plant. It offers all-year-round visual interests, cheering up Vancouverites weary of the city’s wet season. Yellow flowers bloom from March to April, followed by the formation of blue berries multiple times a year, which provide food for bird species such as the American Robin and Cedar Waxwing. In winter, the leaves and stems lose chlorophyll and turn bronze-red, conserving its energy for the next blooming season, while creating aesthetic appeal. The First Nations people, particularly the St’at’imc nation in Lillooet, B.C., have long utilized this plant. They name the plant ts’óltś’el and boil its roots to extract yellow dye for weaving baskets. Although the fruits are bitter and are ‘last resorts’ of food for the Indigenous group, they are sometimes collected to make wild jelly when mixed with sweeter berries in the area. With its high ecological and cultural significance and year-round attractiveness, this plant teaches me to appreciate the ordinary regardless of the weather and to embrace the rain in

Vancouver.

Olivia Yeung

This piece is a commentary on the history of tulips versus the existence of tulips in modern society

today. What we see now is a commercialized and aestheticized bouquet of flowers but what we fail

to recognize is its deep history with the floral market. Upon looking closely at the bouquet of tulips,

one can see that the newspaper used as floral wrap is a news article about the tulip’s history.

People fail to recognize that any flora, object, and everything comes with lineage. Historically, tulip

bulbs used to sell for as much as the price of a house today. From then on, the commercialization

of flowers changed its trajectory permanently. By using a historical newspaper to wrap the bouquet,

it both supports today’s trends within the floral market while also providing more information for

those keen enough to care.

Assignment 2: Case Study on Sacred Landscapes asks students to choose a site of study that they consider sacred and analyze the form, meaning, symbologies, location, orientation, material composition, with a focus on their flora. Sacred landscapes are often described as socio-symbolic aspects of human-environment interaction.

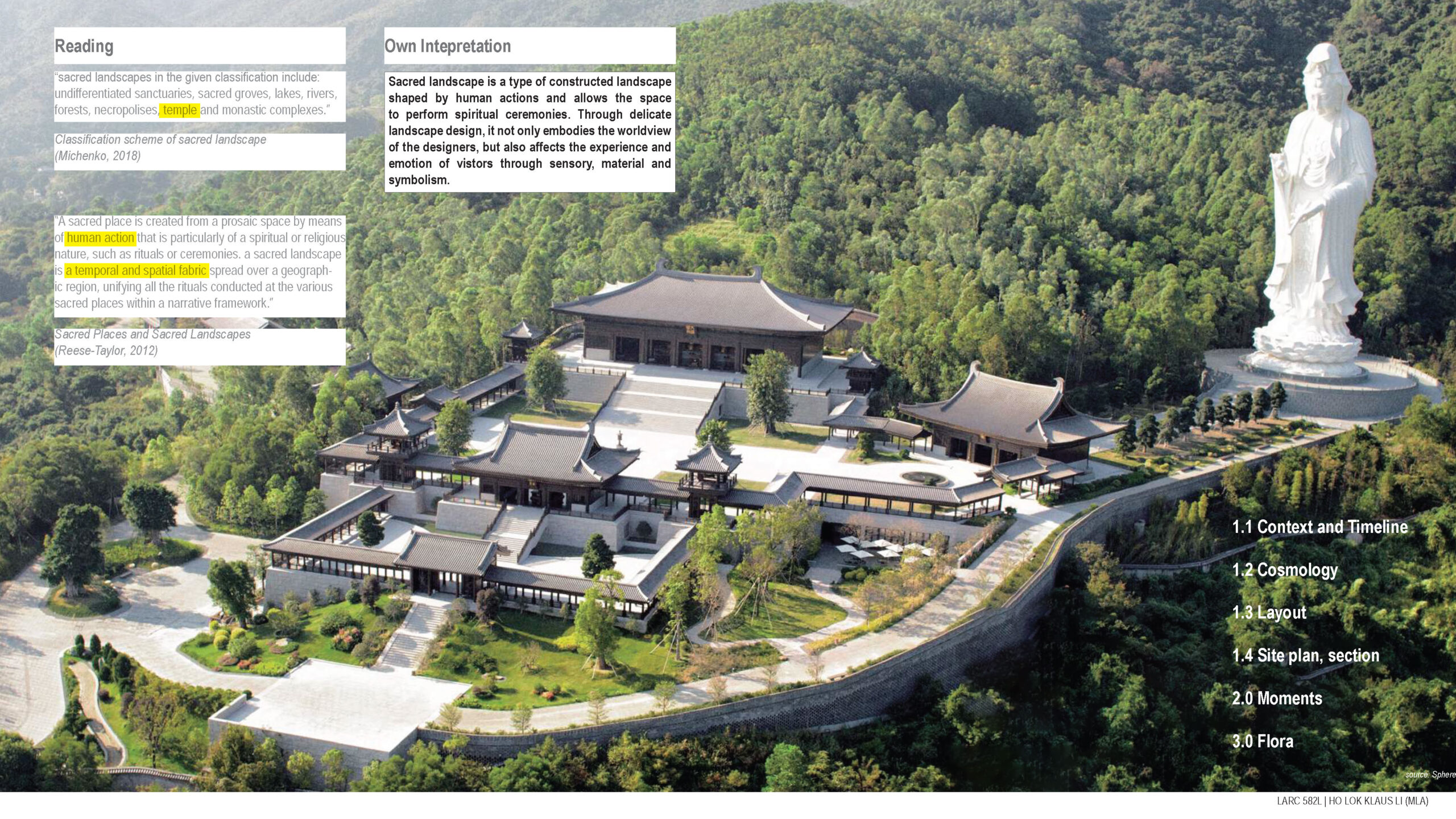

Ho Lok Klaus Li

In the realm of landscape architecture, a sacred landscape is a space shaped by human actions to perform spiritual ceremonies, embodying the designers’ worldviews and affecting visitors’ experiences through sensory, material, and symbolic elements. This definition aligns with perspectives that see sacred landscapes as undifferentiated sanctuaries, sacred groves, lakes, rivers, forests, necropolises, temple, and monastic complexes . By interpreting sacred landscapes through these lenses, it becomes evident that these spaces are designed to foster a spiritual connection, evoke a sense of sanctity, and provide an immersive experience.

Tsz Shan Monastery, located in Hong Kong, offers a fascinating case study of a constructed sacred landscape rooted in Buddhist cosmology. Buddhism, which originated around 500 BCE, spread to China via the Silk Road, influencing various aspects of Chinese society. The monastery, funded by tycoon Li Ka-shing, began construction in 2003 and was completed in 2014, following a series of permission applications, statue erect ceremonies, and spiritual rituals.

The monastery’s design is intricately linked to Buddhist cosmology, emphasizing the journey towards enlightenment and the alleviation of suffering. The layout includes significant structures such as the drum tower, library, residence areas, Guan Yin statue, and study areas. These elements are strategically placed to guide visitors through a spiritual journey, beginning at the entrance and culminating at the Guan Yin statue, symbolizing compassion and mercy in Buddhism.

Granite, predominantly used in natural cleft and flamed finishes, constitutes the primary material of the monastery. The choice of granite not only enhances the aesthetic appeal but also symbolizes permanence and resilience, reflecting the enduring nature of Buddhist teachings. The site is divided into public, Buddhava (space for Buddha), and Sanghava (space for monks) areas, each serving a specific purpose in the spiritual and daily lives of the visitors and monks.

The design of Tsz Shan Monastery encourages visitors to reflect and connect with the spiritual essence of the space. The journey begins at the entrance, where rows of pine shrubs create a sense of care and tranquility. As visitors progress to the courtyard, they encounter Podocarpus macrophyllus trees and a lotus pond, which frame the space and provide a venue for various ceremonies. This area embodies the Buddhist concept of the interconnectedness of life and the importance of maintaining a serene environment for spiritual practices.

In the second courtyard, four Ficus religiosa trees symbolize the Four Immeasurables: loving- kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity. These trees not only enhance the aesthetic beauty but also serve as a reminder of the core Buddhist virtues that visitors are encouraged to cultivate.

The final experiential moment involves walking towards the Guan Yin statue, where Podocarpus macrophyllus trees frame the corridor and direct the visitors’ focus towards the statue. This deliberate design element creates a sense of reverence and emphasizes the significance of the Guan Yin statue in the Buddhist faith.

While Tsz Shan Monastery is a constructed sacred landscape, it effectively conveys a sense of sacredness through its careful design and symbolic elements. The use of materials, spatial arrangement, and integration with the natural environment all contribute to creating an atmosphere conducive to spiritual practice and reflection. This demonstrates that sacred landscapes need not be ancient or naturally occurring; they can be purposefully designed to foster spiritual connections and embody religious principles.

Tsz Shan Monastery exemplifies how landscape architecture and spatial design can create a sacred landscape that embodies Buddhist cosmology. Through its thoughtful layout, material composition, and symbolic elements, the monastery provides a sanctuary for spiritual reflection and learning. This case study highlights that sacred landscapes, whether naturally occurring or constructed, serve as vital spaces for connecting with the spiritual realm and fostering a sense of sanctity.

By examining Tsz Shan Monastery, we gain insight into how constructed landscapes can effectively integrate social, spiritual, and environmental elements to create a holistic and sacred experience. As a non-believer, the sense of sacredness felt at the monastery underscores the universal potential of well-designed sacred landscapes to evoke profound emotional and spiritual responses.

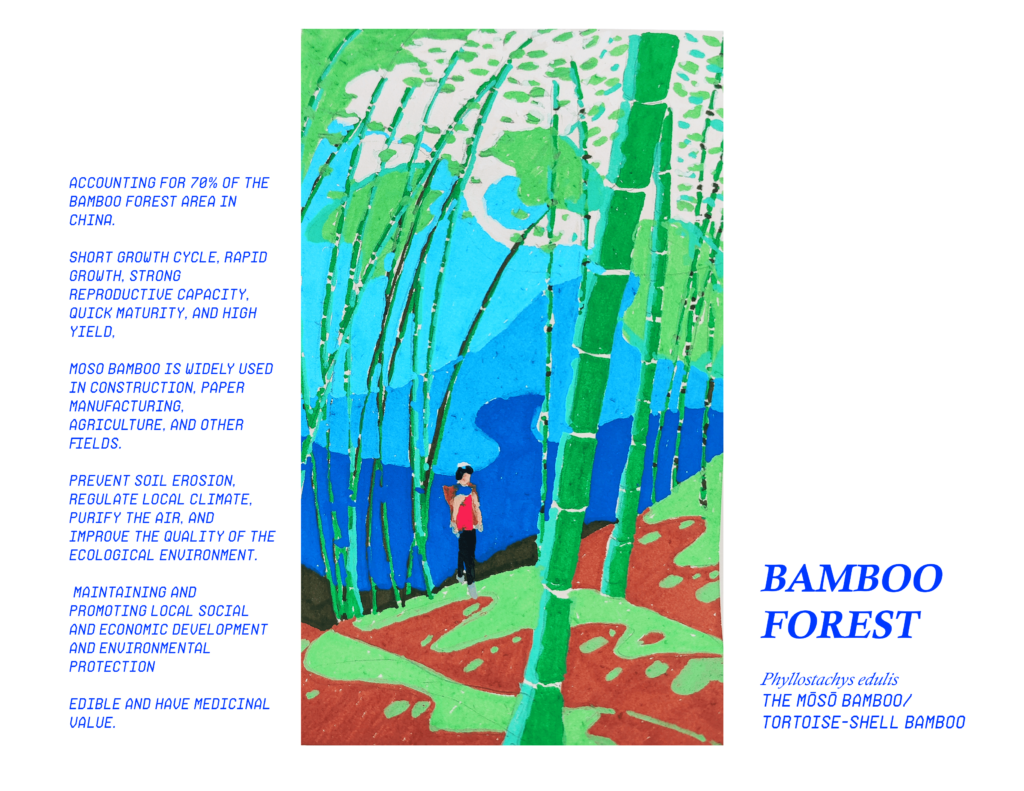

Laura Liu

Reflecting on the significance of feng shui forests in southern and central China, I am struck by the intricate relationship between these sacred landscapes and the communities that have nurtured them for centuries. These forests, often overlooked by urban residents and the wider world, embody a deep cultural heritage and environmental wisdom that offers invaluable insights into sustainable living and ecological balance.

The concept of feng shui, commonly associated with interior design and divination, takes on a profound and practical dimension in these rural settings. Translated simply as “wind” (feng) and “water” (shui), feng shui principles have guided the placement and management of forests to optimize energy flow, protect settlements, and enhance agricultural productivity. These forests are not mere patches of greenery but are integral to the villages’ microclimate, water conservation, and crop cultivation strategies. The careful selection and placement of trees around villages have ensured protection from harsh northern winds, facilitated sunlight for rice paddies, and maintained soil integrity against erosion.

The history of feng shui forests dates back to at least the 3rd Century AD, where they were initially used to safeguard the tombs of emperors. As the Han people migrated south, they adapted these practices to establish villages in harmony with their natural surroundings. The arrangement of villages—situated on auspicious sites with protective mountain barriers and open southern plains—demonstrates an advanced understanding of environmental management long before modern ecological science.

Examining the village of Lihang as a case study reveals the practical and spiritual dimensions of feng shui forests. The village, surrounded by an evergreen and broadleaf forest primarily composed of Chinese fir, bamboo, and Chinese sweetgum, benefits from these ancient woods which serve as habitats for rare bird species such as the white- legged falconet and the blue-crowned laughingthrush. The interdependence between the biodiversity of these forests and the well-being of the villagers is a testament to the holistic approach of feng shui, blending ecological stewardship with cultural reverence. The sacredness attributed to these forests, with shrines dedicated to Earth gods and beliefs in supernatural guardians, reflects a worldview where nature and spirituality are deeply intertwined. This perspective fosters a respect for the natural world that has practical outcomes, such as preventing soil erosion and maintaining water resources, which are crucial for the villagers’ subsistence and prosperity.

Today, as China grapples with ecological challenges and seeks sustainable reforestation models, the principles embedded in feng shui forests offer a promising blueprint. Unlike past efforts that relied on non-native species and monocultures, feng shui forests demonstrate the success of using a diverse array of indigenous plants tailored to local climates. These mature forests, preserved and managed through traditional knowledge, could guide contemporary ecological initiatives, promoting biodiversity and long-term environmental health.

This exploration has revealed how much there is to learn from these ancient practices. The feng shui forests are more than a historical curiosity; they are living examples of sustainable human-nature relationships. By understanding and valuing these landscapes, we can glean lessons that are relevant not just for China but for global efforts in conservation and sustainable development.

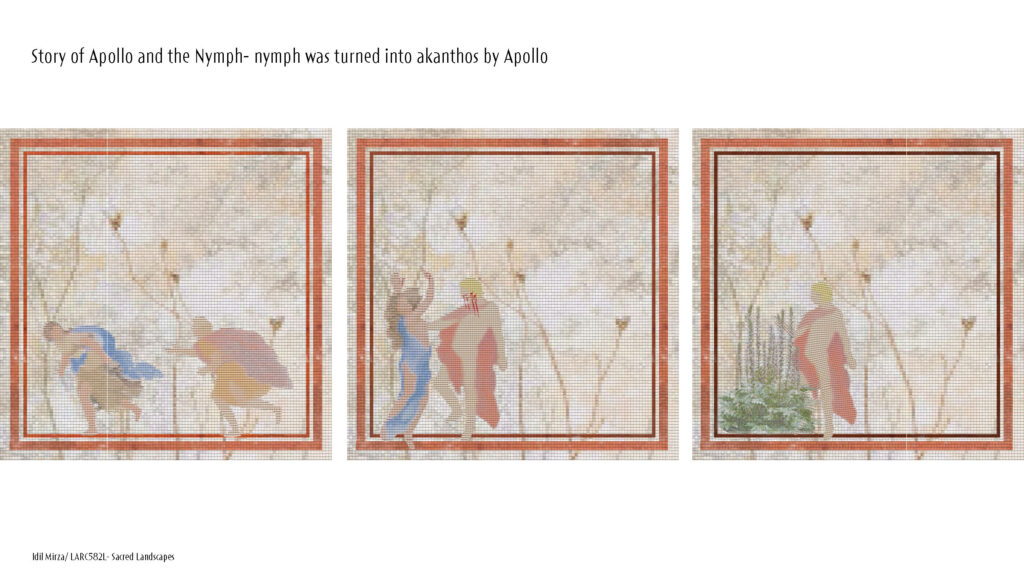

Idil Mirza

Sacredness is an attribute given to the landscape by humans. A landscape by itself does not come to be sacred. It is the experience of the landscape that makes it sacred. More experience, stories and historical layers make the landscape sacred because the landscape becomes life… It inspires, it tells stories and once you step into a sacred landscape you can feel the past lives in the plants, the hills, the topography, architecture, soil. You feel connected. A landscape, an ancient city that still has ruins standing today, that creates and inspires awe with its layered history and culture can be defined as sacred. This rich tapestry of civilizations has contributed to Ephesus’ status as a symbol of historical continuity and cultural exchange in the Mediterranean region which makes it sacred.

The ancient Greek city of Ephesus is located at the point where the Cayster River (Kaystros-Kucuk Menderes) meets the Aegean Sea, now situated in the Selçuk district of Izmir on Turkey’s western coast. Its history spans several millennia, making it a significant site with diverse cultural influences. Ephesus served as a bustling port city where trade, intellectuals, and administrators converged. It witnessed the cultural traditions of three distinct epochs: the innovative Neolithic period, the tumultuous Hellenistic era, and the influential Roman period, each leaving their mark on the city. Moreover, Ephesus endured various rulers and cultural shifts, including Persian rule, incursions by the Goths, and ultimately, Ottoman rule. According to legend, the Ionian prince Androclos founded Ephesus in the eleventh century B.C. The legend says that as Androclos searched for a new Greek settlement, he turned to the Delphi oracles for guidance. The oracles told him a boar and a fish would show him the new location.

One day, as Androclos was frying fish over an open fire, a fish flopped out of the frying pan and landed in the nearby bushes. A spark ignited the bushes, and a wild boar ran out. Recalling the oracles’ wisdom, Androclos built his new settlement where the bushes stood and called it Ephesus.

The plan of the city shows that according to the time it was built this city was way ahead of its time which can also explain why so many different cultures wanted to rule over this area. There is one main route of circulation with 2 main entrances and within that smaller pathways that can take you to baths, houses, theatre and agoras. Most of the Ephesian ruins seen today such as the enormous amphitheater, the Library of Celsus, the public space (agora) and the aqueducts were built or rebuilt during Augustus’s reign which was between 129 BC to 262 AD. Looking at it from the public space point of view the city has so many elements form bustling streets to commercial agora which was the place where people would gather and sell their goods (basically where trade was done), the theatre where the events would take place which could accommodate enormous numbers of people, ritual areas where the ‘holy fire’ was and bathing houses. Water seems to have a very big importance in this geography. As it has been mentioned before Ephesus was a port city, so the economy was tied to water ways. It is one of the first cities to have intricate water pipelines that would connect the water system below ground and above with aqueducts, circulate water in bathing houses etc. There was also a place named stage of agora that was the second agora in Ephesus. It is the government Agora. Political subjects were discussed here, and it was open to public including women and the slaves which shows everyone had a say in how to live in this city to some extent.

During this time the frescos and mosaics were a big element in decorating the spaces and if these are analysed a lot of information on the flora and fauna can be found. Looking at those I have picked the strawberry tree (andrakhnos) and bear breeches (akanthos). Strawberry tree is an evergreen shrub, native to the Mediterranean region, and western Europe, grows wild in woodland and field edges. Ovid, who was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus, included the Strawberry Tree in the list of fruits descended from the “The Golden Age” a time when people were content with food that grew without cultivation. Strawberry tree fruit is rich in therapeutic properties and has tons of medicinal value, but this is not depicted in any of the frescos. However, it is a prominent plant that is seen as a visual throughout the ancient city. According to folklore, discovering a branch of the Strawberry

Tree bearing three berries was considered a harbinger of good fortune. The striking colors of the Strawberry Tree are concentrated in its living parts. Like many Mediterranean trees, the Strawberry Tree, possesses numerous dry branches—lifeless, often diseased or damaged, characterized by dark brown color and classic cracking. The tree’s life is intricately defined by these dead or alive branches, which extend from the trunk to the roots, and the tree is able to isolate entire sections of itself to conserve energy.

The acanthus plant, also known as bear’s breeches, is a perennial with thick, serrated leaves native to the Mediterranean and parts of Asia. It thrives in diverse environments, from mountainous edges to coastal islands. This plant is among the oldest in its region and holds the distinction of being Greece’s national flower. Since ancient times, people have used the acanthus for its sacred medicinal properties and healing attributes where it was used to treat open wounds. In Mediterranean cultures, it symbolizes enduring life and immortality. On the other hand, though, in Christianity, its leaves symbolize pain, sin, punishment, and death. While acanthus leaves initially adorned ancient Greek architecture, their prominent use was not until the Roman period. They became integral to the decorative elements of Corinthian and Composite order columns, showcasing intricate designs on capitals, friezes, and other architectural features which also suggests that in Ephesus it could have been the Romans that integrated this plant symbol in the columns of the temples and other architectural elements.

Hannah Whitlaw

By Shinde’s notion of the sacred, a sacred landscape embodies mythological stories, legends, rituals, and spiritual values that are deeply rooted in the local culture and tradition. In learning more about my own ancestral cultures in upland Scotland, I have unearthed these very values resting with an island in Orkney.

Eynhallow is a tiny island, less than 1 square kilometer in area and rising only a few feet above sea level, which sits in a narrow channel between two larger Orkney islands – Mainland and Rousay. Few maps exist of the island, however land surveys and historical accounts place features such as stone monastery ruins, an ornithological research site, old dikes, and a seal colony at specific locations as marked on the plan. The south part of the island has been described as rough pastureland with low-growing grasses and herbs and a sandy shoreline, while further north transitions to peaty moorlands with sphagnum moss, heathers, and bog plants before reaching rocky outcrops along the shore. The waters around Eynhallow are laden with fierce tides and dense fogs which have made the island largely inaccessible to humans. A boat runs only once a year for visitor access to the island from Rousay.

Eynhallow is often called “Holy Island,” referring to it having been the site of a monastery centuries ago, built in the 12th century and used my Norse, Scot, and English monks. All that remains of the monastery are stone ruins as the island has been uninhabited by humans since the 1850s, and it often presumed to only have been seasonally occupied for years before that. What is left the monastery is now mostly inhabited by Northern Fulmars – a species of seabird who breed on the island, nest in the cliffsides and small openings of the ruins, and are visited infrequently by scientists who monitor their population.

One of the reasons for the lack of human presence on the island coincides with another name for it – “Vanishing Island.” Eynhallow is frequently rendered invisible from even the closest shores of Mainland and Rousay by thick sea mist, fog, and strong tides which can rush up to eight knots in Eynhallow Sound and are known to have claimed many boats over the years. In legend, the island is invisible altogether to mortal eyes, especially those actively seeking it. These conditions have left ample room for mystery in the minds of those who have lived near Eynhallow. The parts of island which I am drawn to and view as the sacred basis of Eynhallow, are the imagined and mythological landscapes which are intertwined with it. In addition to the aforementioned names, Eynhallow is also referred to as “The Enchanted Isle” and “Isle of Mystery” – and these are the names that make it sacred to me. The island fits into multiple stories embedded within Orkney folklore, but is intimately tied to the mythological beings known in Orkney as Finfolk.

The Finfolk are an amphibious sea people who can step out of the water onto land as they choose and live comfortably between the two worlds. They are known as powerful sorcerers who can be both threatening and benevolent, controlling the weather to reward fishermen with pleasant sea waters or punish them with treacherous storms. Finfolk have been represented both as beautiful humanoid beings and as sea monsters, though the most prolific understanding of their appearance is that they look enough like humans to deceive any people watching them, having fins that drape like clothing over their bodies. The underwater dwelling of the Finfolk, known as Finfolkaheem is regarded as their place of origin and their ancestral home and is described as a fantastic underwater palace with massive crystal halls surrounded by ornate gardens of seaweed lit by the bioluminescent glow of tiny sea creatures at night. Its buildings are made from coral and pearls the size of boulders are scattered the land, leading the way to the palace. Its great halls are said to be decorated with moving draped curtains whose colours move and dance with the currents and are sometimes said to be cuttings from the northern lights.

In the summer, the Finfolk left Finfolkaheem to live in their summer home of Hildaland, which today is the land we know as Eynhallow. Meaning “Hidden Land”, Hildaland was a paradisiacal island said to be either invisible, hidden just underwater, or surrounded by magical fog – making it rarely glimpsed by humans. It’s said to have been guarded by monstrous whales and Finmen with tusks. Hildaland was cleared of enchantment by an angry farmer whose wife was carried away in a boat by the Finfolk. The farmer swore revenge, defeating the obstacles presented by the Finfolk and finding the island where he performed a religious ritual to claim the land of the Finfolk and transformed it from Hildaland to Eynhallow – banishing Finfolk to spend their years at their underwater residence. And though Eynhallow is now visible to the human eye, its relative inaccessibility and its ecologies still shroud the landscape in enough mystery that many still believe the island is magical and that the Finfolk live in the surrounding waters.

With minimal built structures present and little documentation of Eynhallow, it is difficult to say how the architecture of place makes the island sacred. Instead, what makes this landscape sacred is the very geologies, ecologies, and hydrologies which allow it to be enveloped in mystery, myth, and stories which still run throughout Orcadian and greater Scottish folklore and imaginaries.

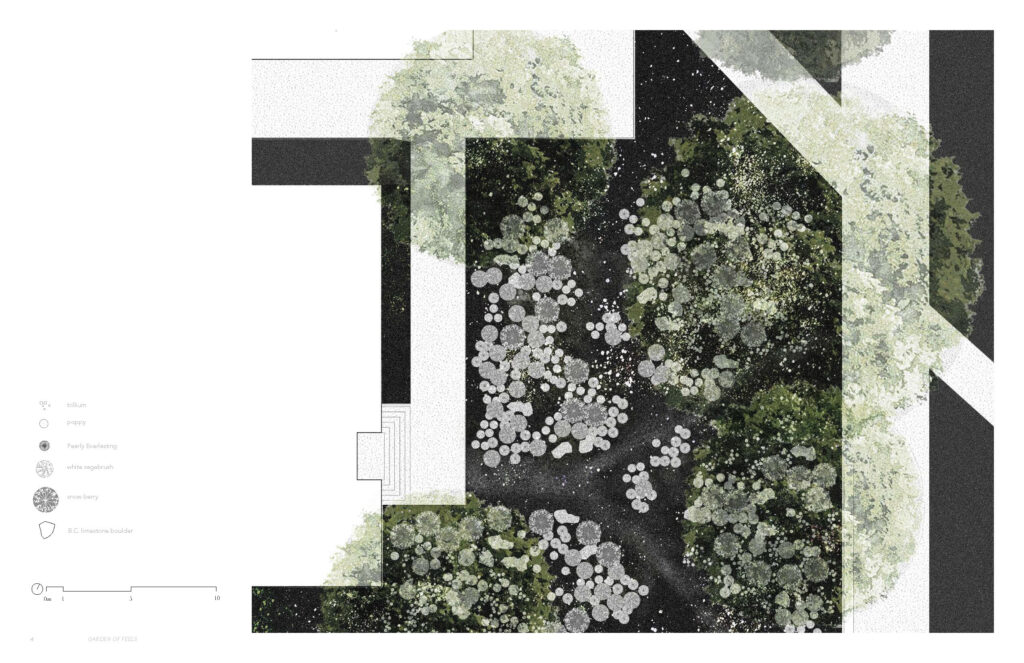

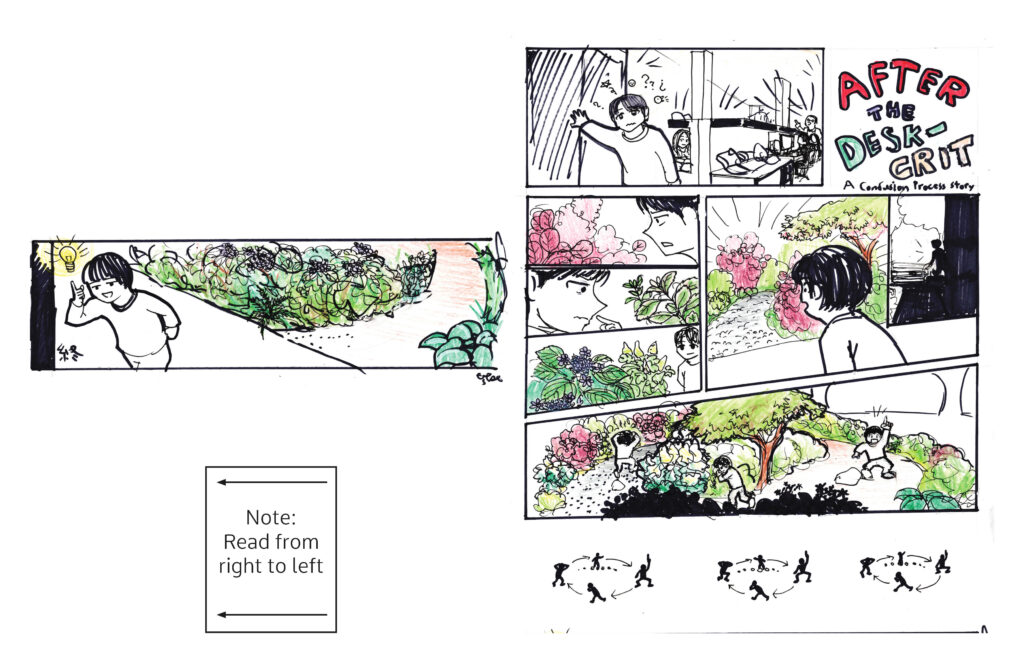

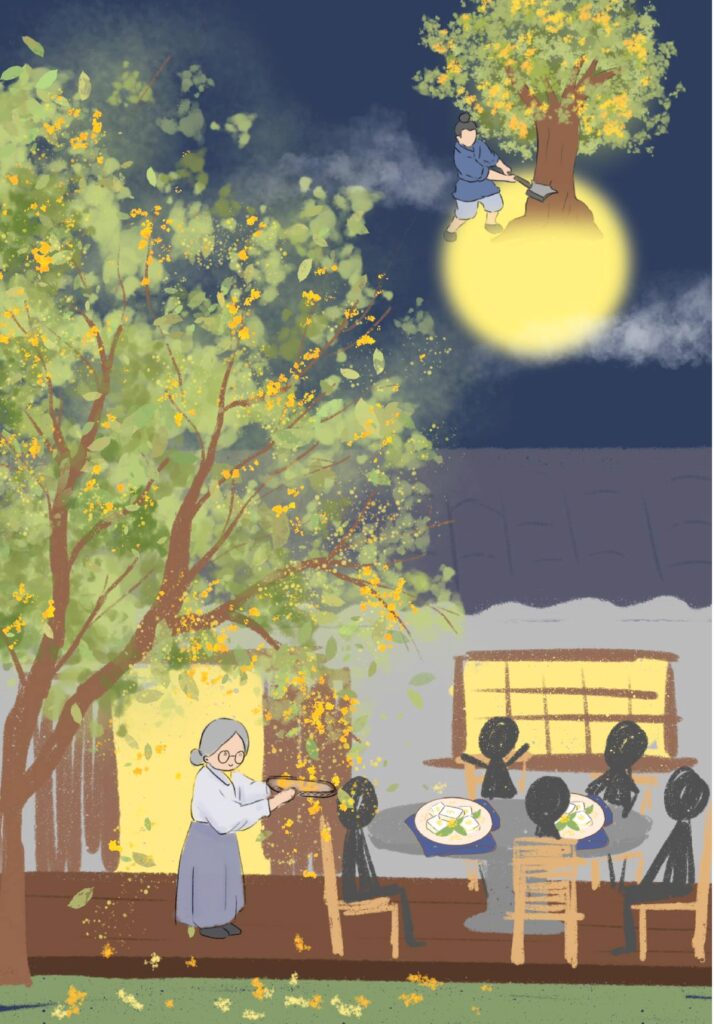

Assignment 3: Garden of Feels asks students to design a garden inspired and/or reflecting a specific emotion or feeling (ie. anger, happiness, confusion, sadness, surprise) of their choosing. Using storytelling as a technology, the assignment builds upon the previous assignments to communicate a feeling through the design of a garden. Using the Landscape Annex as the site, students are asked to engage, consider, and communicate ecological conditions, socio-cultural conditions, garden design implications and the positionality and/or intention of their storytelling perspective.

Garrett McGill

Project Description:

It is 2am and you have just spent the past 18 hours motionless in a chair 24 inches from your computer screen. Your eyes burn from the mix of florescent overhead lighting and computer screen. Alone and done for the day you pack up, descend the stairwell and push through the annex front door. With a crisp cool breeze the haze in your eyes from artificial light vanishes, you look out, silver foliage illuminates the ground, shadows and shapes you can’t quite make out glimmer in the moonlight. Your shoulders relax, muscles loosen and you take a deep breath suddenly more grounded, recentered and brought back down to earth from the worries of studio.

The moon for thousands of years has been celebrated for its mystery and special energy. It represents a time to gather with community and release unwanted energies. The moon is a gateway to create change in our life, for letting go, cleansing and releasing what doesn’t serve us anymore. Each culture on Earth across time sees the Moon in a unique way, each with its own stories about the Moon and its various faces.

The moon garden as a typology has origins in India, to be enjoyed at dusk or nighttime with respite from the heat of the sun. Key elements include white and silver foliage that reflect moonlight and nocturnal blossoms that attract nighttime pollinators. Moonlight alters human color perception differently than sunlight, accentuating the colors of some flowers/foliage more than others. This brings out unique tones that are not visible in daylight or under artificial lighting.

The plants I have selected all have unique relationships with time and renewal, as explained in further detail on the back of each shadow box. Each plant is drought tolerant, relevant to Vancouver’s hotter dryer summers in the face of climate change. I chose plants that spread by rhizome, self seeding or suckering, so that the edges of the planting beds begins to blur with time, and shift based on changing desire lines.

Reflection:

This semester I have come to acknowledge and understand the ways in which contemporary landscape discourse and practice, represents plants through reductive Western cultural and taxonomic standards. This convention abstracts plants from their biophysical and relational contexts – which have emerged over millennia and through deep physical, emotional and spiritual relationships with plants. We can relate to and document plants in ways that acknowledge their sacredness and agency by first questioning conventions of our Western academic milieu. SALA’s planting design course exemplifies this convention asking students to produce reductive excel sheets of plant lists with a specific focus on the ‘functional’ quality of plants. This ‘functional’ quality is often evaluated with ecosystems services, which inherently reduces plants and their ecosystems to the direct and indirect benefits provided exclusively to humans. This is not a reciprocal approach. By investing the time to ask deeper questions in search of the embodied histories of plants, we can begin to be in better relations with plants. We cannot acknowledge a plants sacredness without understanding the political, social, cultural and often contested histories of the plant. The Assignment 01 ethnobotanical narrative when I chose the Opium poppy, exemplified this. Without seeking the ethnobotany of this plant, I was ignorant to hundreds of years of geopolitical tensions, livelihoods dependent on the poppy and the countless references to the poppy and its embodied histories appearing in pop culture. Now every time I have passed a poppy blooming this month, I think of its journey from the middle east to Vancouver and the countless lives it has touched.

Landscape designers can approach kinship with plants by first reflecting on plant-people relationships. Kin, are one’s relatives, and for designers to be in kinship with plants, they must speak of and use a plants name, as they would their cousin – not an abstract object with aesthetic qualities. To treat a plant as a relative, one approach is to first understand the naming of plants. This is important because names are key elements that can trace pathways of ancient plant knowledge. Histories of plant introduction, abundance, cultural roles and potential utility can be referenced in a plant’s indigenous name. Nancy Turner states that cultures and language have been selective in their botanical lexicons. Most people can only name a small portion of the plant species found in their regions, and thus to name a plant species relates directly to its overall cultural importance for a given community. A respect-based design lens helps landscape designers position themselves in relation to, and part of the complexity of life. Designers can learn from the teachings of Kincentric Ecology, the way indigenous people see themselves as members of a broader ecological family, sharing common ancestry and origins.

This class has given me the tools to not only disrupt the Eurocentric visual narrative modes of documentation commonplace in our academic setting, but also in professional offices. As an intern I can take initiative to offer alternative representational techniques, that invite deeper human kinship and relationships with plants. Having worked in a few architecture and landscape architecture offices in Canada and Europe, I’ve become familiar with the “lunch n’ learn” culture of our industry. At most offices, interns are asked to lead a lunch n’ learn about the work they have contribute to / learned while in the office, other times interns are asked to speak about their personal research. After this course, I am inspired to use this opportunity in practice to share the core teachings of this class. Interns often have the exciting task to build scale models, what if there was an opportunity to explore ethnobotanical representations of plants commonly specified by the office, similar to that of building a scale model? I could lead a lunch n’ learn that references my Assignment 2 case study and my Garden of Feels. I could then share with the office a few ethnobotanical representations I created for some of the plants we are working with on my project team. I believe it is important to create a ethnobotanical representation in the office and show the team that there are real world applications for this thinking – and that this work is not simply just a cute academic project, but one with serious implications for how we see and discuss plants.

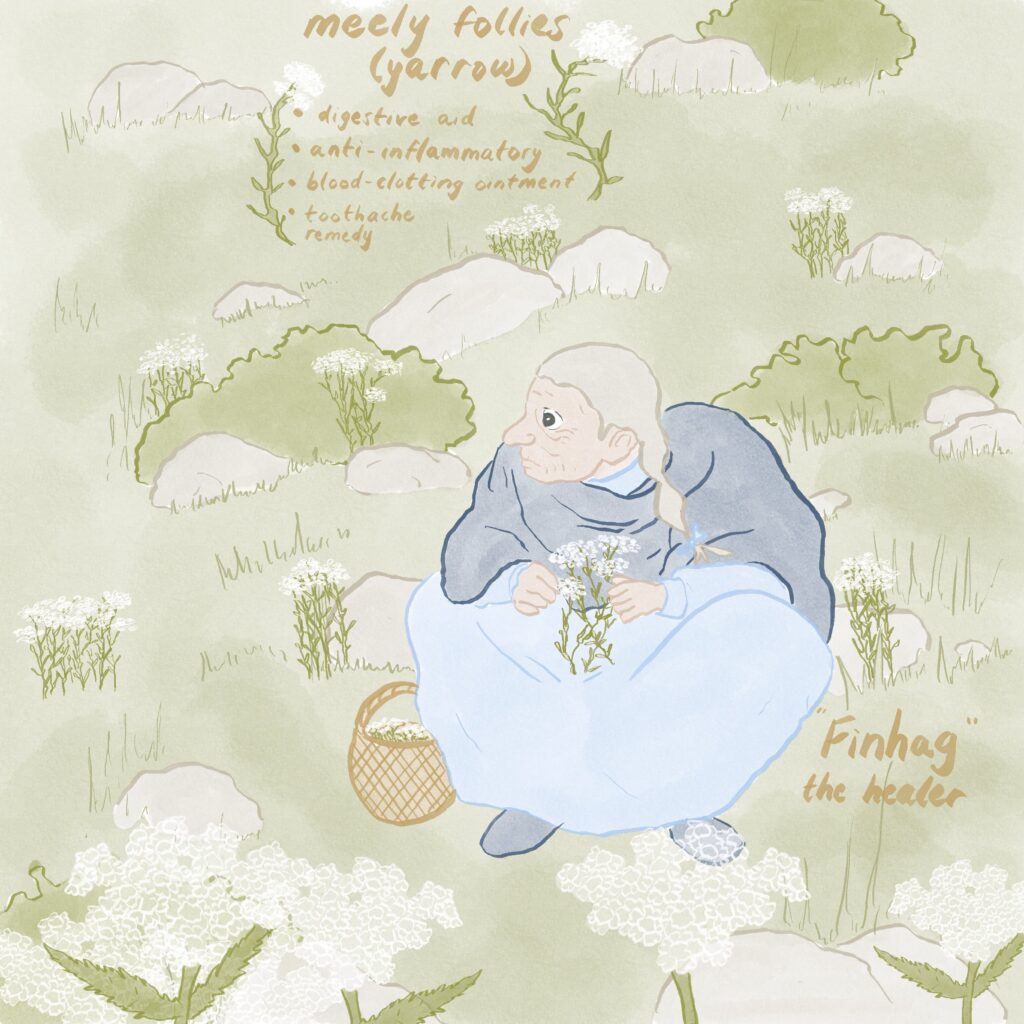

Idil Mirza

This garden proposes a space next to the Landscape Architecture annex building for students and anyone who needs a break and to calm the nerves or to wind down from the business of the day, the life, the time to be mindful and take a breath. We all are at different stages of our lives and go through different experiences each day so the calmness being referred to in this project is not just to alleviate the general stress form design school but to actually stop and take a break from our fast-paced lives. Plants used in this project are yarrow (Achillea millefolium), lavender (Lavandula angustifolia), big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), creeping rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Prostratus’) and snowbrush (Ceanothus velutinus).

The garden will have 3 types of calmness: communal, transitional and solo. Communal calmness is about engaging in activities as group to calm down, unwind and relax. This area is similar to an open meadow area with lavender and yarrow as well as big sagebrush and evergreen snowbrush and rosemary on top of the trellises and near the communal seating area. Baskets can be woven from big sagebrush, lavender and yarrow can be collected together and this area can also collaborate with the already existing food garden. Transitional calmness is more walking based; however, it relies on slowing down the pace. Same plantings exist in this area however the planting is done in a way where there are more undulations especially with the evergreen plantings. Finally, the area of solo calming is nestling in between the existing trees and as far as possible from the traffic of Agronomy Rd and hidden away from the Main Mall traffic with the help of snowbrush. The evergreens here are the tallest so that it creates the calming solo experience for the users of the space as well as the rosemary that can be used as curtains on top of the proposed trellises for people who truly want to separate themselves and calm the mind.

You can create bundles and dry with the lavender, as a group or as an individual. You can take the calmness with you to your home or to studio space. The plant was historically used to improve sleep, calm the mind, relieve pain both physically and mentally… Since it engages with the sense of smell it is also tied to boosting memory, making new memories and even recalling the memories that is tied to this smell. The scent brings serenity and calmness due it being a sedative. The smell makes you calmer however, it is not just the smell but also the texture of this plant that adds a wispy element to the landscape that can interact with weather conditions such as wind. The plant is a semi-evergreen perennial that also provides food for bees.

Snowbrush is an evergreen shrub that can grow up to 3m tall with tiny textural leaves and with the dainty off white flowers. The entire plant has aromatic properties, when leaves are crushed, or it is exposed to sunlight on a warm day it emits a cinnamon like smell which where the names cinnamon brush or tobacco brush are also coming from. It has been used as a cleansing solution in sweathouses by the indigenous peoples. This plant will surround you when you need solitude so crush the leaves and let the scent take you and calm down…

Close your eyes and touch… Rosemary drapes over the trellises like a curtain. You can touch the leaves or crush the leaves to release the scent of the plant and take a deep breath. It is an evergreen shrub with little lilac flowers that bloom in spring and summer but also since it is a dense plant and an evergreen it provides greenery during winter months as well. You can sit under, collect the leaves and take them to studio, to your home and even cook with it, you can make tea from it, and you can propagate it at home as well. Moreover, it provides habitat for bees, butterflies and hummingbirds.

The yarrow is a herbaceous perennial that is native to Europe, Western Asia and North America. In many cultures it signifies strength. All parts of the plant can be used for its medicinal properties to help stopping bleeding to healing wounds and upset stomach due to its sedative and anti-inflammatory properties. It flowers in spring summer and attracts butterflies, ladybugs and bees. By the indigenous peoples the yarrow was also believed to reinforce their healthy boundaries. The term they use is to ‘feel yarrow-y’ which describes a feeling of snuggled under a under a blanket in a comfortable position, feeling safe and warm…Yarrow is a big umbrella shield…It provides calmness through comfort and strength.

Finally, the sagebrush… It is a native evergreen shrub, and it is a survivor plant which can live up to 100 years that can grow from 6 inches to 15 feet. Indigenous peoples have been using sagebrush for smudging before or after going into the sweat lodge to get rid of the evil and negative energy. To calm the mind and body…If you crush the leaves, you will be left with a spicy bitter smell similar to a rosemary, a fresh cool winter like scent. Gather the leaves together to make sage bundles or weave the branches together to make a basket… Empty your mind for a bit and calm down…You can take the bundle to studio perhaps or just enjoy the presence of this plant and watch it dance with the wind…

The calmness of this garden can be experienced with being in the space, engaging with it, transitioning between these spaces and can be taken with oneself to continue the calming effect even when one leaves the garden.

Neil Popko

The feeling of being held is an intrinsic part of human experience, providing a deep sense of security, comfort, and support. This feeling, which can come from physical touch, emotional connections, or a sense of being surrounded by something larger than oneself, is essential for mental and emotional well-being. As we navigate through life’s challenges, creating and fostering spaces that evoke this feeling of being held becomes imperative. Nature, with its inherent beauty and serenity, offers a profound sense of grounding and stability, reminding us of the cycles of life and the interconnectedness of all living beings. This reflection explores how we can relate to and document plants in ways that acknowledge their sacredness and agency, and how landscape designers can approach kinship with plants to enhance our connection with the natural world.

Plants as Kin: Recognizing Connections

Plants are more than mere biological entities; they are integral parts of ecosystems with their own forms of agency and sacredness. Fireweed (Chamerion angustifolium), plantain (Plantago major), tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia cespitosa), climbing honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum), and lamb’s ear (Stachys byzantina) are examples of plants that hold significant ecological and cultural value.

Fireweed is a often a volunteer species, the first to reappear in areas devastated by fire. Its ability to thrive in harsh conditions symbolizes resilience and renewal. Documenting fireweed involves recognizing its role in ecosystem recovery and its cultural significance to indigenous communities who use it for food, medicine, and rituals. By understanding its ecological functions and cultural stories as a plant that “rises from the ashes”, we can honor its sacredness and agency.

Plantain, often considered a common weed, has remarkable medicinal properties. Its leaves can soothe insect bites, wounds, and inflammations. Documenting plantain should go beyond its botanical characteristics to include its traditional uses in herbal medicine and its role in sustaining local biodiversity by tolerating harsh environments like roadsides and cracks in the sidewalk. This holistic approach acknowledges its value and agency in both natural and cultural landscapes.

Tufted hairgrass is a vital species in grassland and woodland ecosystems, providing habitat for various wildlife. Its dense tufts can prevent soil erosion and improve water quality. Recognizing tufted hairgrass’s contributions to ecosystem health highlights its agency and the sacred role it plays in maintaining environmental balance. Documenting it should involve capturing such interactions with the environment and to all forms of life it shares space with.

Climbing honeysuckle offers nectar to pollinators and has a rich history in folklore and traditional medicine. Its sweet fragrance and vibrant flowers connect people to sensory experiences of nature often overlooked in traditional forms of representation. Documenting climbing honeysuckle should involve not only appreciating its ecological relationships but also consider the more than two dimensional forms of representation that could be used to communicate a more holistic essence of this being.

Lamb’s ear is known for its soft, velvety leaves that offer tactile comfort. It can serve as a metaphor for the gentleness and care that nature provides, but also using its softness as a form of resistance against the hardness of current urban landscaping paradigms. Documenting lamb’s ear should include its role in gardens as a sensory plant that invites touch and connection, emphasizing its contribution to human well-being and emotional health.

Alternative Approaches to Landscape Design

Refocusing the botanist lens on sacredness, agency and relationality has taught me to reconsider my connections to the plants I design spaces with. Hope and strength can come from fireweed. Plantain can soothe me. Hairgrass can bring balance. Honeysuckle can protect me and lamb’s ear can hug me. Considering the more than human capacity of these plants (and more) connects me to something bigger than myself, and I feel like I am being held. My appreciation and respect for all the ways I am

supported, connected and familiar with the plants around me deepens my stewardship and care for an approach to landscape design that is interested in decentering humanness from the making of a landscape. By being held by this ecological “net”work, I am inspired to hold space for plants in return. In this context, my approach to landscape design is less concerned with the maintenance and preservation of a place, but rather careful observation of the unexpected changes a site goes through. When a plant shows up that wasn’t considered in the initial design, instead of removing it, I believe it could be embraced as an opportunity for reflection and connection to the larger context surrounding the site.

Spaces that begin to celebrate the energy, fragrance, and tactile qualities of plants can better nurture our emotional well-being and foster a sense of belonging. Emphasizing that plants can offer comfort and support, (like lamb’s ear) can transform landscapes into healing landscapes for both humans and the land itself. In dealing with our double crisis of late-stage capitalism and climate change, careful slow observation of a changing landscape is our way to leave our busy stressful lives, be held in the natural connections that surround us, and ground us in knowing nature has and always will be here. By working with plants to create sanctuaries that promote mental and emotional healing, we are reinforcing the idea that softness and gentleness are strengths we need to practice. Relating to and documenting plants in ways that acknowledge their sacredness and agency and by appreciating the unique qualities and contributions of plants we deepen this sense of connection, respect and compassion.

Eakin Sawada-Tse

The proposed garden design outside of the Landscape Architecture Annex seeks to embody the feeling of confusion, reflecting on the productive yet anxiety-rich environment of the landscape architecture studios inside the building. Specifically, the garden is a representation of the individual’s internal cycling between states of confusion and clarity, mirroring how a landscape architecture student would process new and complex information after a desk critique with a landscape architecture instructor. In essence, the garden symbolizes the process of handling confusion.

To achieve this effect, the garden is comprised of a circular loop with three distinct zones. The first zone embodies the confused state of being, characterized by dense plants species that have either confusing physical/ textural characteristics (e.g. smoke bush for texture, variegated Japanese euonymus for colour) or ambiguous names (e.g. false-lily-of-the-valley). The second zone is a stepping-stone pathway that links the first and third zones. This symbolizes the individual’s process of contemplating/calming down after the initial confused state. Plants here are a mixture of confusing plants and those that indicate a certain reality relative to the former (e.g. Jogasaki lace-cap hydrangea with fertile flowers exposed over the false/sterile ones). The third zone is a wider space with mostly plants vaguely resembling the native ecosystem of the Vancouver area (e.g. vine maple and sword fern), representing a moment of ideation and clarity. From here, two paths go onward: one that connects back to the confusion zone representing doubt and lingering confusion, and the other representing the individual’s renewed confidence and readiness to continue design work.

Students featured:

Dean Anesi

Patricia Dawn Bueno

Tatianna Duncan

Samuel Kohlmann

Ho Lok Klaus Li

Wenyao Li

Laura Liu

Qiushi Liu

Zhengyu Liu

Garrett McGill

Idil Mirza

Alex Mok

Neil Popko

Eakin Sawada-Tse

Hannah Whitlaw

Kaity Windrem

Olivia Yeung

Joseph Zhou

Divine Ndemeye is a landscape designer, artist, educator, and alumni of the SALA Master of Landscape Architecture program. She is the Founder and Principal of Remesha Design, as well as the founder and Co-Director of the Black+Indigenous Design Collective. She is also the host and producer of the Design unmuted podcast, a platform that elevates marginalized voices in design, art and all things creative.