While Vancouver is often found near the top of lists of the world’s most liveable cities, it can also be found among the world’s most unaffordable. Despite this, the population of the city is expected to grow by several hundred thousand by the year 2060. How will we house these additional residents, while keeping that housing within financial reach? This was the challenge levied to the fall 2019 Master of Urban Design cohort by their professor Patrick Condon. The results of their exploration are now available on a website, as well as in a publication. Presented as a tour through Vancouver, their plan examines affordability and housing at a variety of scales, from the neighbourhood block to the entire city.

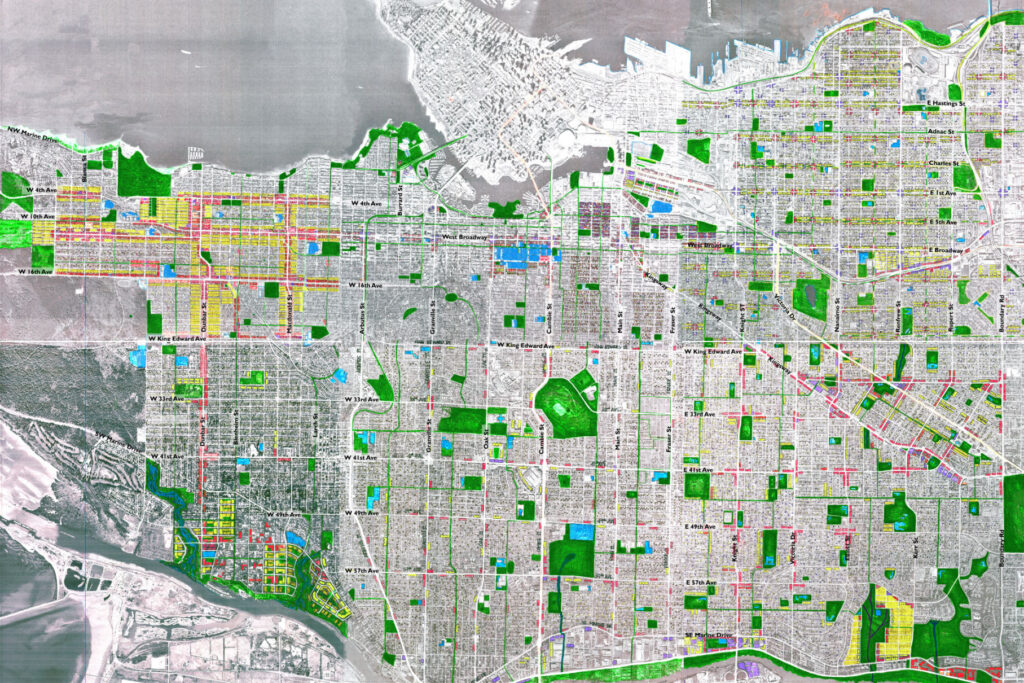

The fifteen students (representing seven different countries) in the MUD cohort began with an analysis of Vancouver’s foundational issues, taking equity, ecology, and history into consideration. The city was then divided into six quadrants, with each assigned a team of students to envision what the area could look like in forty years. Each quadrant measured about 25 square kilometres, with job and population targets based on existing development. The resulting map shows areas of infill, a green network of spaces and streets, and a transit system featuring 15 minute-or-less service.

The scale of study was then increased, with each student creating an in-depth, prototypical design for a four- to six-block area. These designs were created with potential city-wide application in mind. The themes explored range from intergenerational living, to laneway activation, to green infrastructure. The result is a plan for over 1.4 million residents, with housing for a range of incomes.

This comprehensive plan is compiled in a publication, “Imagining An Affordable Vancouver for 2060: A city-wide Plan for an Equitable Vancouver.” Physical copies are available for purchase, and a free ebook is available for download.

We spoke to MUD student Kaenat Seth about her experience working on this project, and how the MUD program influenced her ambitions.

Why did your class take on this ambitious project?

As a cohort which was mostly international, we couldn’t fathom the extent of the housing problem in Vancouver until we couldn’t find houses for ourselves at an affordable price. This led to us getting a hang of how deep this problem is rooted. Once we were able to relate to the issue, the statistics that showed how huge the jump in population numbers is going to be, showed to us that this problem more than anything else needs to be addressed. I think travelling around the city to wonderful parts like Strathcona and then to the Downtown East side showed the stark difference between the living conditions for most people. The project set out to achieve an equitable, livable and affordable city for all and this idea resonated with everything we studied and wanted to achieve with urban design.

As an international student, how was this project relevant to your experience back home?

The problem of housing affordability takes a toll on every economy, whether big or small. In a massive country like India where the population statistics are so overwhelming, the solutions for this problem, if any, seem sectarian and almost never aim to encompass the livability aspect or address concerns about life outside one’s home. What I learned during this project was that these facets are not mutually exclusive. The experience of thinking about the complete needs of the residents of a city first, and their housing structures after, made me realise that this approach can turn around the fate of the poor and homeless in places like small towns back in India, where they would otherwise be doomed to cram in informal slum settings. But the ideas of designing each parcel for multiple units was an experience during the years of design work in India that I could draw from. So this project not only helped me capitalize on the skills I had previously learnt but also nurtured so many new ones that changed my perception of the way urban design works.

Did you have difficulty coming up with a reasonable response to the problem?

Although the predicament seemed arduous at first, as we read Patrick’s works and began digging deeper, we discovered that the issues at hand were comprehendible and to a certain extent we could imagine our solutions changing the fate of the city. The doubling of the city’s population in the coming five decades was inevitable and initially we couldn’t envisage the idea that this population could be absorbed into the existing fabric of the city. It was only after all 15 of us were assigned one of six quadrants of the city and we went into the lanes and saw for ourselves that there was so much potential. The massive lot sizes housed more or less 2-4 people and were monotonously spread across the entire city. The biggest problem was the lack of physical space for the city to expand into and thus the entire burden of this new population falls onto the existing land and amenities. The city systems that support the people however, seemed broken and sporadic. These were some of the challenges we looked at however, with Patrick’s guidance and from what we had learnt in the program, we were able to turn these challenges into fruitful discussions.

Housing affordability is a problem world-wide. Did your class find solutions?

Agreeably, many of my classmates had studied and worked on this problem in the context of where they were located. However, the problem here in Vancouver is a very different one. The city is bound by water on three sides unlike any other place in the world and there is barely any land for it to expand into. This forced us to flip the lens and look into what potential the existing fabric has.

The first step was to design for continuous network systems across the city which could hold up the increased density. We studied the frequent transit network, the lost streams, the streetcar streets which were the backbones of the city and completed the broken connections. We also sought to weave the civic amenities throughout so that the current and future residents were always within a short walk from anything they needed.

One big move we made was to provide work opportunities within this fabric, such that all residents could develop a balanced live-work equation and would only have to go to their backyards or as far as a few blocks in order to get to work. This coupled with the increased densities on the existing parcels would ensure that businesses like mom and pop stores could thrive and the economy could rise without disrupting the character of the City of Vancouver.

What is your hope for the future of the MUD program?

The MUD program for us was a way to see what problems plague the north-american cities and although we all had seen a different version of the same ones in our journeys with design, this process gave us all new perspectives. This program didn’t try to form new opinions for us but built on what we had already seen and learnt and that I think was one of the strongest aspects of it. All the courses were woven together to give us a unique experience of seeing a region with different lenses, zooming in and out, to fully make sense of what goes into the process of city-making or rather re-making. I hope that in the future, the program is able to collaborate more with the City and get students to be a part of the activities happening around since for us, the False Creek redesign project where we presented to City-council was ground-breaking since we got to actually work with the community, put our ideas across and get feedback from people who are responsible for the future of the city. This program will forge the designers of the future world, and I think that working collaboratively in the studio on real world problems will not only drive their creativity but also fuel the discussions that will bring forth the ideas that will change the way we live.

What is your hope for your own career and how has the MUD program influenced your ambitions?

Since the program was only a year long, but had so much packed into it, it has invigorated in me a passion for learning more and working to build up the communities around me. I have a background in architecture and so my outlook towards the issues of city-building was very different at the outset. After exploring the design world through the MUD program, I am now better equipped to configure anything from the minutest detail in a room, to how the entire region around it works to enhance it’s experience. It was through the MUD program, that I learnt our thoughts shape our spaces, and our spaces return the favor too. This mutual evolution of cities and it’s residents have led us to this moment in time, where we are about to redefine this coexistence. In my pursuit to define cities through their residents, I want to be able to work alongside the best and to induce a bigger change in the way our future will be determined especially after seeing a crisis alter our very basic systems. My hope is to use these skills and be able to bring a measurable change that creates value for people around the globe. Through this program, I have gotten the opportunity to work for Patrick Condon and my current research work with him inspires me to devote my life to the purpose of building an equitable future and as he says, the coming 40-something years will be laborious but I am sure the journey and outcomes will be worth it.